By Ibrahim Suffian

The blue flags emblazoned with the scale of justice hang limply in the humid air. Speeding cars drive by ragged remnants of blue banners and flags strewn by the roadside – relics of the watershed Malaysian elections on May 9th 2018. Life moves on, unrelenting in to the future. Many analysts, including this writer, were blindsided by what happened.

While some may have claimed to foretell the future a month ago, the surveys of all organizations showed that a significant proportion, as many as one-third, of Malaysians refused to disclose their choices to pollsters and politicians alike, preferring to say they were “undecided”. This is amply evident in the many polls produced by various organizations leading to election day. The truth is, voting for the Opposition, particularly among Malay voters, was something one does not speak about openly, for fear of losing practical benefits, privileges or even friendships. This can be explained by the “spiral of silence theory” which speaks of the tendency of people to not openly express views or opinions they feel are divergent from the community they belong to.

Now in the wake of the event, we are left to figure out what went through the minds of millions of voters that day – relying on preexisting research, countries with similar political contexts, as well as analyzing the raw results from the election.

Detailed data that would shed light on how Malaysians decided may not be available for many more weeks and would then require careful analysis that seeks to reveal how people from different ethnicities, sub-regions, age groups and income strata made up their minds. Yet ample information exist from work already done to explain how the sentiments turned to a silent revolution that overturned a six decade long dominant party and turned it into opposition overnight.

Some have postulated the outcome of the election on one or two critical factors, citing public backlash over the Goods and Services Tax or the 1MDB scandal. That alone does not explain the near perfect storm that terminated Barisan Nasional’s hold on power. While reform hungry Malaysians and supporters of Pakatan Harapan were right to celebrate their years of toil upon reaching victory, this journey resembles that of other peoples who have toppled decades of dominant political parties such as the People’s Revolutionary Institution in Mexico, the Grand National Party in South Korea, the Kuomintang in Taiwan, and Golkar in Indonesia.

There are at least six critical factors that led to the result. The first three are embedded in our political system. Regular elections, which have conducted here since 1955, have served as a source of mandate and validation of the party holding power — the Alliance, then expanded and renamed Barisan Nasional — since Independence. These periodic events, though flawed and unfair to the then Opposition, became part of the national political culture. Second was the continuous presence of Opposition parties, though usually weak and inhabiting the fringes of the political spectrum, they were a source of potential competition for the ruling party. Third was the pragmatism among the Opposition parties to cooperate in order to maximize the votes – an uphill task in Malaysia’s heavily gerrymandered, first past the post system – yet coalitions or electoral pacts among opposition parties had been a feature in our elections since 1964, such when the Socialist Front was formed to challenge the then Alliance, or the unnamed electoral pact in 1969 among nearly all of the Opposition parties which took two states from the Alliance, as well as garnering nearly one-half of the popular vote.

Yet it took a fourth factor – the consistent pressure for election reform that achieved the first breakthrough in 2008. Tentative efforts by the BERSIH coalition of civil society organizations and their allies in the Opposition to demand more transparency in the conduct of elections by the Elections Commission managed to gain popular support by the mobilization of a number of large rallies, the first in late 2007.

These initial steps delivered modest improvements – transparent plexiglass ballot boxes and the counting of ballot papers at the polling room (rather than being transported to a centralized counting center), and eventually, in 2013 the use of indelible ink to prevent repeat voting. Groups such as BERSIH and independent media organizations served as a critical force in awakening ordinary Malaysians to the power of the vote, which when coupled with technology and knowledge connected people with one another in a manner that left them invested in the political process. It soon became not just another election, but a sacred ritual to determine the path to be taken by the nation.

Achieving the Tipping Point – the Leadership Factor

In Mexico, it was Vicente Fox, in the former Czechoslovakia, Vaclav Havel, in the case of Malaysia, it needed not one but two charismatic leaders to cement a coalition that was strong enough to challenge the dominant ruling party. Both led splinter groups that left Barisan Nasional to form new parties that cooperated with existing political parties. In 1999, the then jailed Anwar Ibrahim formed a pact that eventually broke the Barisan Nasional’s two-thirds supermajority. It needed another splintering of the ruling party before the final blow could be delivered. Former premier and strongman Dr Mahathir Mohamed quit UMNO in February 2016 and formed a new party later in the same year, joining the preexisting Pakatan Harapan coalition.

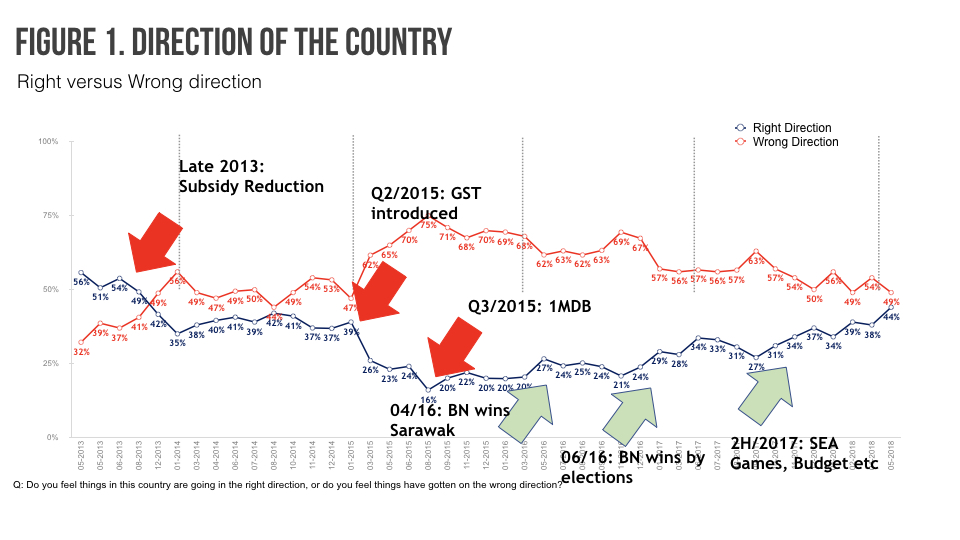

The fifth factor was a slew of critical issues that caused widespread dissatisfaction with Barisan Nasional. The removal of subsidies in late 2013, the introduction of the Good and Services Tax in April 2015, and finally the sordid details emerging from the 1MDB scandal, all taking place when a large majority of Malaysians felt squeezed between stagnant wages and rising costs. These issues had eroded support for BN since late 2013, but the Opposition was unable to make headway among more conservative, BN-leaning voters, as seen in the 2016 Sarawak state elections and two by-elections, in Kuala Kangsar and Sungai Besar, that same year. Our data from mid-2015 onwards showed Barisan Nasional appeared to make some gradual recovery as can be seen in the chart below. While the Opposition had been articulating various populist promises and criticism of BN failings before, none had the impact as when it was articulated by the former premier, particularly among the Malay swing voters that was needed to cross the line. Seen in this context, the data suggest that Dr. Mahathir’s leadership factor was critical in lending legitimacy and credibility to the solutions proposed.

The fifth factor was a slew of critical issues that caused widespread dissatisfaction with Barisan Nasional. The removal of subsidies in late 2013, the introduction of the Good and Services Tax in April 2015, and finally the sordid details emerging from the 1MDB scandal, all taking place when a large majority of Malaysians felt squeezed between stagnant wages and rising costs. These issues had eroded support for BN since late 2013, but the Opposition was unable to make headway among more conservative, BN-leaning voters, as seen in the 2016 Sarawak state elections and two by-elections, in Kuala Kangsar and Sungai Besar, that same year. Our data from mid-2015 onwards showed Barisan Nasional appeared to make some gradual recovery as can be seen in the chart below. While the Opposition had been articulating various populist promises and criticism of BN failings before, none had the impact as when it was articulated by the former premier, particularly among the Malay swing voters that was needed to cross the line. Seen in this context, the data suggest that Dr. Mahathir’s leadership factor was critical in lending legitimacy and credibility to the solutions proposed.

Leadership allows for complex issues and concepts to transcend barriers, so it could be understood by the masses. It works both ways for good and bad leaders. Barisan Nasional and Najib Razak’s problems began when Dr Mahathir began articulating his criticism in the characteristic straight talking fashion he is well known for. Eschewing complex vocabulary, Mahathir called Najib a ‘thief’ rather than a kleptocrat. More critically, Mahathir helped ordinary, conservative and nationalistic oriented Malay Muslim voters overcome their fear of voting the Opposition – perhaps, just enough to make the numbers to win the election that night. Najib on the hand, resorted to ridiculing his opponent for being in politics again at the age of 92. This generated more sympathy for Mahathir rather than diminish his appeal.

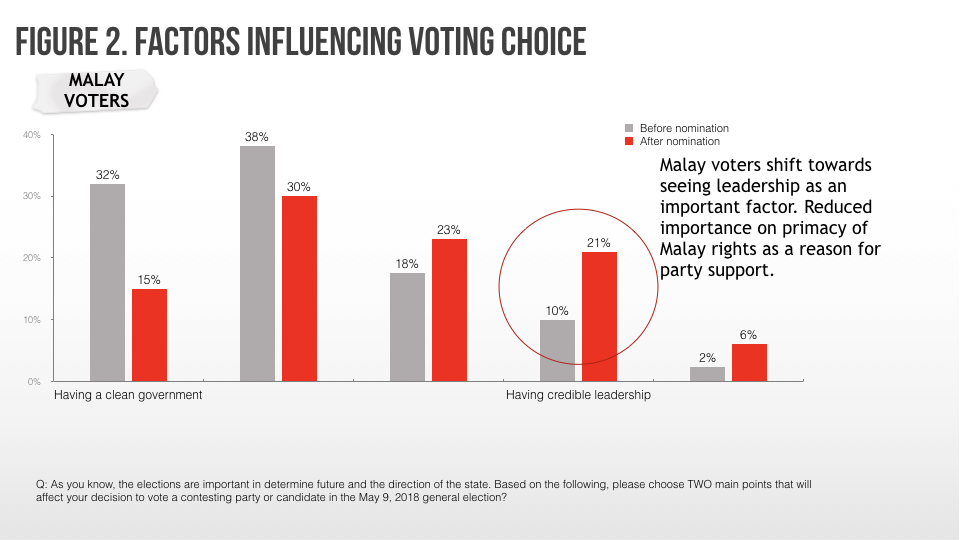

Our survey data from the days leading to the election showed that a significant number of Malay voters began to set aside the importance they held for “preservation of Malay rights” and moved towards choosing “having a competent national leadership” during the course of the 11-day election campaign. This is significant because it meant Barisan Nasional’s primary appeal to its core Malay base had become eroded. In our view, this was the crucial factor that enabled PH to achieve the tipping point among Malay voters – their trust in Dr. Mahathir’s leadership.

Finally, the outcome would not be complete if not for a few last minute own goals by Barisan Nasional that enraged the voting public – all of which took place in weeks and days leading to election day: the gerrymandering proposal, a law on “Fake News”, the Registrar of Societies disbanding of Dr Mahathir’s party, calling a mid-week election day ostensibly to depress voter turnout, and promising tax relief for young voters and increase in cash handouts – all probably pushed undecided voters to the brink and brought them out in droves early in the day.

One self-inflicted factor however deserves special mention – James Masing’s dismissal of several senior Parti Rakyat Sarawak leaders in late April 2018 created a voter revolt in the Bidayuh and Iban areas within lower Sarawak, along with internal problems in other parties delivered eight unanticipated parliamentary seats to Pakatan Harapan, thus allowing for the coalition to have a sizeable enough majority to form a stable federal government.

May 9th 2018 was the culmination of the efforts of many groups and individuals who, for the hardships and sacrifices they endured, deserve to be called patriots. It was many factors both pushing and pulling towards the outcome, none could do without the other. Winning the battle over Barisan Nasional was one challenge, our hope is that this victory will be translated into tough but meaningful, sustainable, systemic reforms that mark the beginning of a democratic and inclusive political order – one that unleashes the true potential of Malaysia – its diverse talent and cultural capital.

Ibrahim Suffian is a co-founder and programs director of Merdeka Center for Opinion Research, a leading public opinion polling and political surveys organization in Malaysia.

Ibrahim Suffian is a co-founder and programs director of Merdeka Center for Opinion Research, a leading public opinion polling and political surveys organization in Malaysia.