On March 12th 2018, Parliament proceedings descended into raucous heckling when Selangor Menteri Besar Dato Seri Mohamed Azmin Ali directed a question to the Prime Minister about the effect of the 1MDB debt issue on interest payments and he responded with a flippant, “the water issue in Selangor is even more critical.”

Quoting an international news report last month, which stated that Malaysia had spent 12.5% of its revenue on interest payments for the national debt in 2016 compared to 9% in 2009, Mohamed Azmin asked if the 1MDB debt issue affected the rise in national debt interest.

“The report says that this year we are expected to spend RM31bil of revenue just to pay interest, and this is the same as two-thirds of (the total) GST collection.

Has the 1MDB debt issue affected the rise in our debt interest or is there a more responsible reason for this?” asked Mohamed Azmin.

After a few minutes of heckling by Federal Members of Parliament, the Prime Minister responded that it was not a question of the quantum of national debt, but the ability to repay it and that “Singapore’s national debts are bigger than ours and their repayment abilities are also existent”.

Needless to say the internet exploded as netizens responded in anger and disbelief at the manner in which the Prime Minister and Federal MPs dismissed such a valid and pertinent question by Mohamed Azmin.

The issue at hand is not whether Singapore or Venezuela or any other country can repay or not but rather why is Malaysia spending so much of its revenue on repaying debts? And if so what debts are we repaying?

The question does not arise if the country can repay, the question is why our GST, taxes and everything else that we are made to pay to the government is used to repay debts that we are not fully aware of.

A point to note is that the ability to repay these debts rises from the rakyat’s pockets. As Mohamed Azmin has pointed out we are paying 2/3 of the GST collected for debts incurred by an overspending and careless federal government.

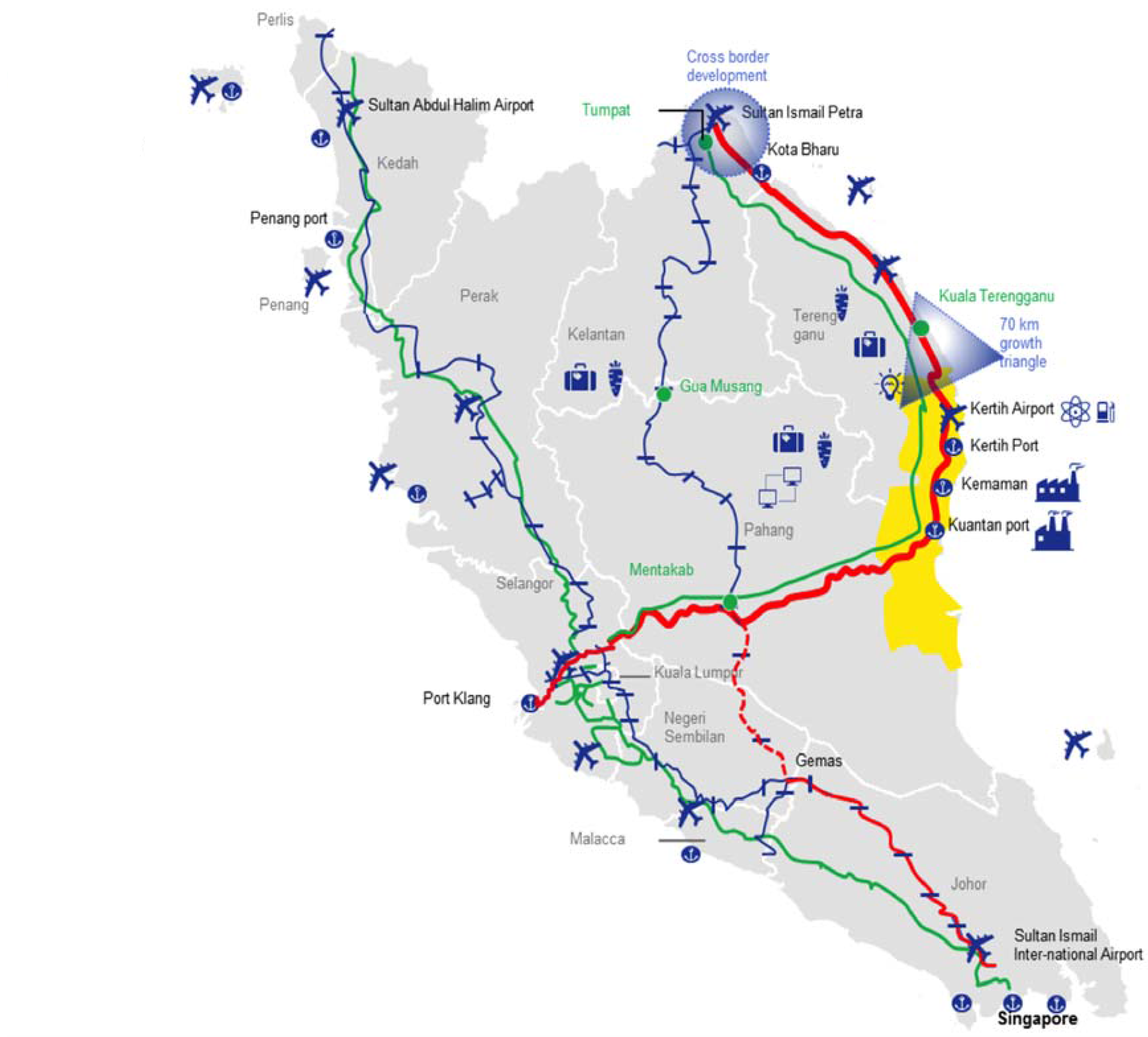

A prime example of how the Malaysian government is currently overspending is the ECRL project. It is one such infrastructure project that will heavily burden the rakyat in terms of debt in years to come as the project lacks transparency and accountability. This is one of those future generations will pay for.

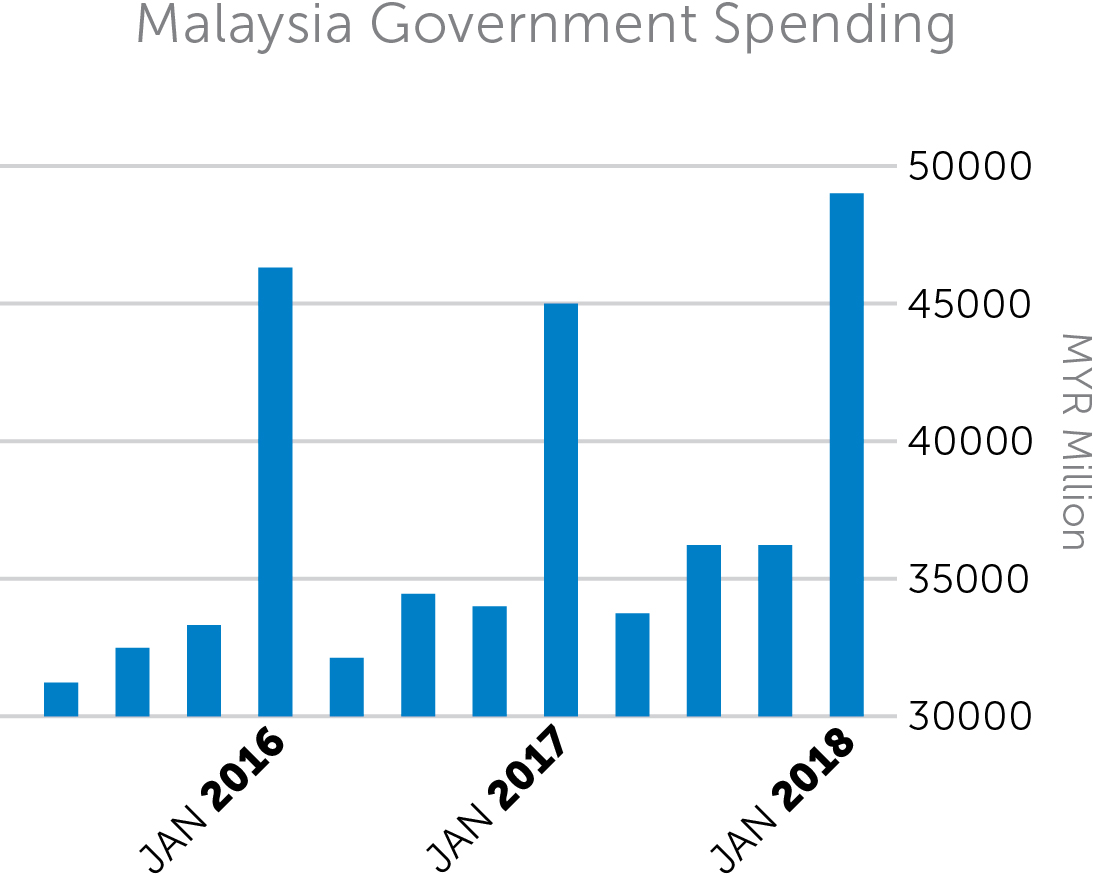

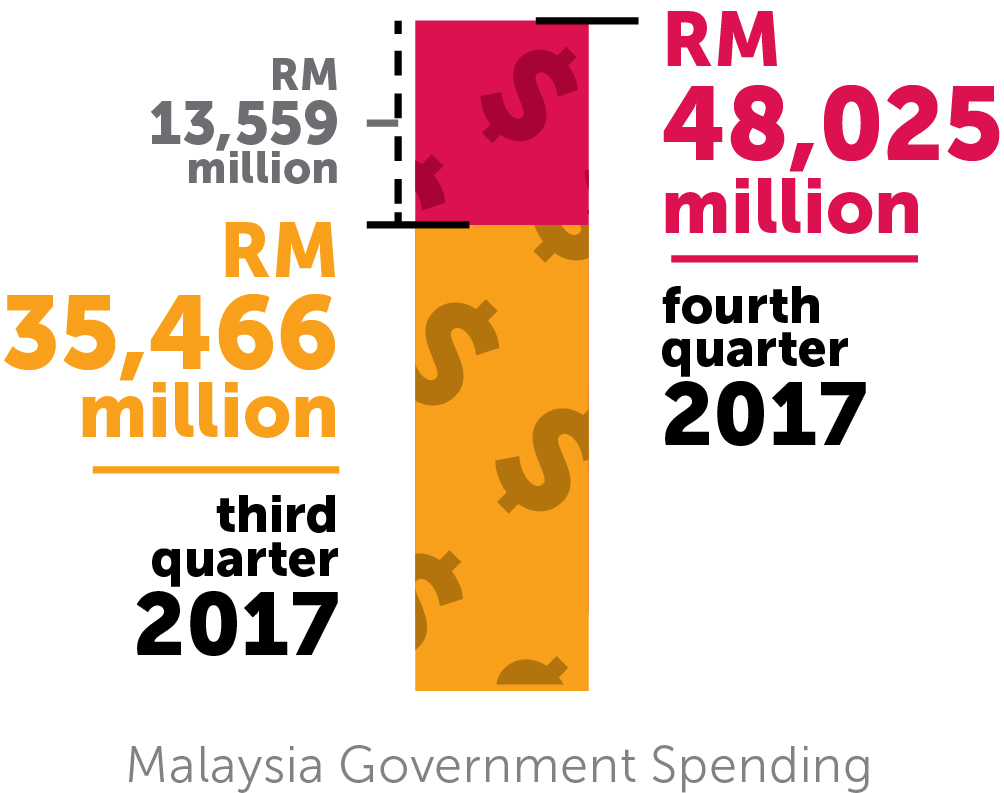

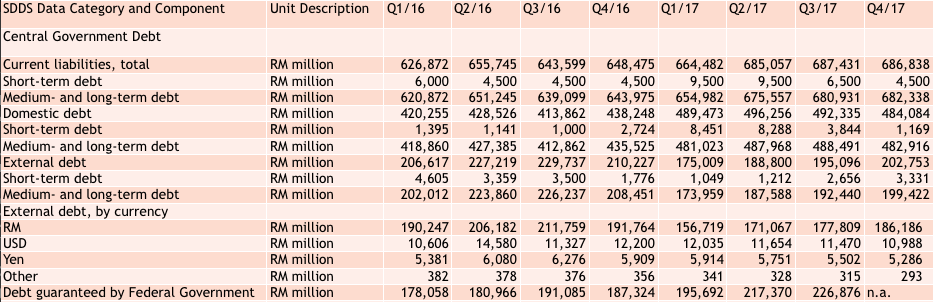

The increase of RM 13,559 million in just one quarter is certainly very alarming especially when the total government debt as of end June 2017 stood at RM 688 billion or 50.9% of the gross domestic product (GDP).

Government spending refers to public expenditure on goods and services through policies like setting up budget targets, adjusting taxation, increasing public expenditure and public works or infrastructure projects.

Disproportionate funds

The issue of overspending raised comments from various quarters including Former United Nations assistant secretary-general Jomo Kwame Sundaram, Dr Francis Loh, formerly a professor of politics at Universiti Sains Malaysia and Wan Saiful Wan Jan, the former CEO of the Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs (IDEAS), all of whom were concerned with government spending, sighting the East Coast Rail Line (ECRL) project.

Overspending by Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) and disproportionate allocation of development funds has led to the official government debt increase.

Recommending that allocations to the PMO be slashed to lower rising debt, Jomo said most infrastructure spending is not on the federal budget and often involves dubious public-private partnerships further reducing transparency and accountability as witnessed in the recent rush to start the ECRL (East Coast Rail Line).

Lacks transparency

Mega-projects such as the ECRL, Tun Razak Exchange, and Bandar Malaysia should be scrutinised by an independent bipartisan parliamentary committee chaired by a member of the opposition party for transparency purposes.

The appointment of the Chinese state-owned enterprise for the ECRL project, China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) was however done via direct negotiation method and not on an open tender basis this pre-empts transparency.

If the 688km ECRL which costs 55 billion ringgit fails to generate the expected level of demand and return on investment, it can put the government highly in debt with China.

Huge interest

Some 85% of the ECRL project costs will be funded by China’s Exim Bank through a soft loan at an interest rate of 3.25% per annum and the rest through a sukuk programme by local banks.

At a rate of 3.5% per annum, the interest bill for the project will be huge. Although interest repayment of the loan only begins after a seven-year moratorium, the government will have to subsidise this project which it can ill afford because it is also involved in several other multi-billion ringgit port construction projects while the repayment of those loans will also come calling about the same time.

At RM 80 million per kilometre, it has been slammed by critics as the costliest rail project ever. The government claims that the total costs include planning and design costs and that it includes the tunnels that need to be dug and the difficult terrain that needs to be traversed.

A property newspaper compares similar rails in developing countries.

In Kenya, Mombasa to Uganda is estimated at RM 7.37 billion (RM61.42 million per km), in Bangladesh, Dhaka to Jessore is estimated at 14.65 billion ringgit (RM68.14 million per km) in Ethiopia, Awash to Weldia is estimated at 7.12 billion ringgit (RM18.07 million per km).

It’s interesting to note that rails in Kenya and Bangladesh include the costs of bridges and other infrastructure and that the Ethiopian one is built 986 metres above sea level and through tricky terrain, all of which cost lower than Malaysia’s ECRL.

Malaysia is borrowing money from China in order to pay a Chinese company to do the job, and after seven years, we still need to pay back the loan plus interest to China. Not only does China get back its money immediately in the form of payment for the work done by CCCC, it will get more money from us when we repay the loan.

It does not matter whether the ECRL is profitable or not, we still have to repay the loan. The risk and liability are completely on the shoulders of Malaysian taxpayers and zero on China.

Questionable viability

The commercial viability of the project has also been questioned. The forecast being the ECRL, despite running through less industrialised parts of Malaysia, will carry almost 60 million tonnes of freight per annum by 2035. This is amazing because even KTM Bhd, which has rail networks in the more industrialised and densely populated west coast of the peninsula, carries only about six million tonnes of freight per annum. If we fail to achieve this projected freight tonnage, will the project still be financially feasible or will taxpayers have to pay a huge subsidy for the ECRL?

Cautionary tale

The ECRL is part of the many projects under China’s Belt and Road (BRI) initiative, that is building infrastructure and boosting regional connectivity and trade across strategic maritime and land routes. China plans to invest 750 billion US dollars in BRI countries over the next five years. Malaysia is one recipient of this initiative.

In the case of Sri Lanka, China provided loan worth 1.2 billion US dollars to build port Hambantota. This initiative has been beset by problems. The Hambantota port did not have an accompanying industrial zone or other local businesses to drive demand and the port struggled to attract ships and cargo volumes.

In the end it was a loss-making infrastructure and continued consuming massive amounts of national revenue to operate and maintain.

Last July, Sri Lanka’s Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe proposed to China’s Ambassador Yi Xianliang a debt-for-equity swap that would see the Hambantota port and the Mattala airport go to Chinese companies in exchange for 1.2 billion US dollars’ worth of debt relief. China agreed.

Another burden

It is therefeore crucial for the government to look at its expenditures and seek out ways to exercise spending discipline and to relook at areas in which it can save by re-prioritising expenses in areas that incur high expenses.

If Malaysia’s debts continue to rise, including taxes, it is the everyday man on the street who will be paying the price for poor fiscal management

It would also bode well for the current federal government to humbly remember who actually repays all these debts.